by Priti David

Original Source: https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/women-at-the-wheel-in-the-nilgiris/

“You can purchase everything in a shop today. But clay pots used in religious rituals by our tribal communities can only be made by us women potters of the Kota tribe,” says Sugi Radhakrishnan. She is 63, and from a long line of women potters in Thiruchigadi, a tribal hamlet, which she refers to as ‘Tirchkaad’ – the Kota people have slightly different names for their settlements. The hamlet is in Udhagamandalam taluk, near Kotagiri town in Tamil Nadu’s Nilgiri district.

At home, Sugi is usually dressed in the signature attire of Kota women – a thick white sheet tied like a toga called dupitt in the Kota language, and a white shawl called varaad . While working in Kotagiri and other towns, the women and men from Thiruchigadi don’t always wear the traditional clothes that they do wear when back in the hamlet. Sugi’s oiled hair is twisted into a horizontal hanging bun in a style unique to the women of her tribe. She welcomes us into her small pottery room adjacent to her home.

“There was no formal ‘teaching’ of how to make a pot. I watched my grandmothers’ hands, the way they moved. Shaping the cylindrical pot into a circular one requires hours of smoothening with a wooden paddle on the outside, while simultaneously rubbing with a smooth round stone from inside. This also decreases porosity, and the stone and paddle must move in harmony so as not to develop stress cracks. Such a pot cooks the most flavourful rice. And we use the smaller-mouthed ones for sambhar . It’s very tasty, you should try it.”

In the Nilgiri mountains of southern India, only women of the Kota tribe have been engaged in the craft of pottery. Their numbers are small – the Census (2011) says there are just 308 Kota left in 102 households in the Nilgiris district. This though is contested by the community elders, who say they number nearly 3,000 (and they have appealed to the district collector for a proper survey).

From the ceremonial extraction of the clay at grounds close to the settlements, to the moulding and shaping, planing and firing, it has been women at the wheel. The men usually do no more than fashion the wheel. In the past, women made pots not only for religious purposes, but also for daily eating, cooking, storage of water and grains, for clay oil lamps and pipes. Before stainless steel and plastic came up from the plains, the only pots used in these hills were clay ones made by the Kota.

In a country where pottery is mostly a male domain, this is unusual. There are very few other documented lines of women potters. The Madras District Gazeteer , 1908, in a section on ‘The Nilgiris’, says of the Kota: “… they now act as musicians and artisans to the other hill people, the men being goldsmiths, blacksmiths, carpenters, leather workers and so forth, and the women making pots on a kind of potters wheel.”

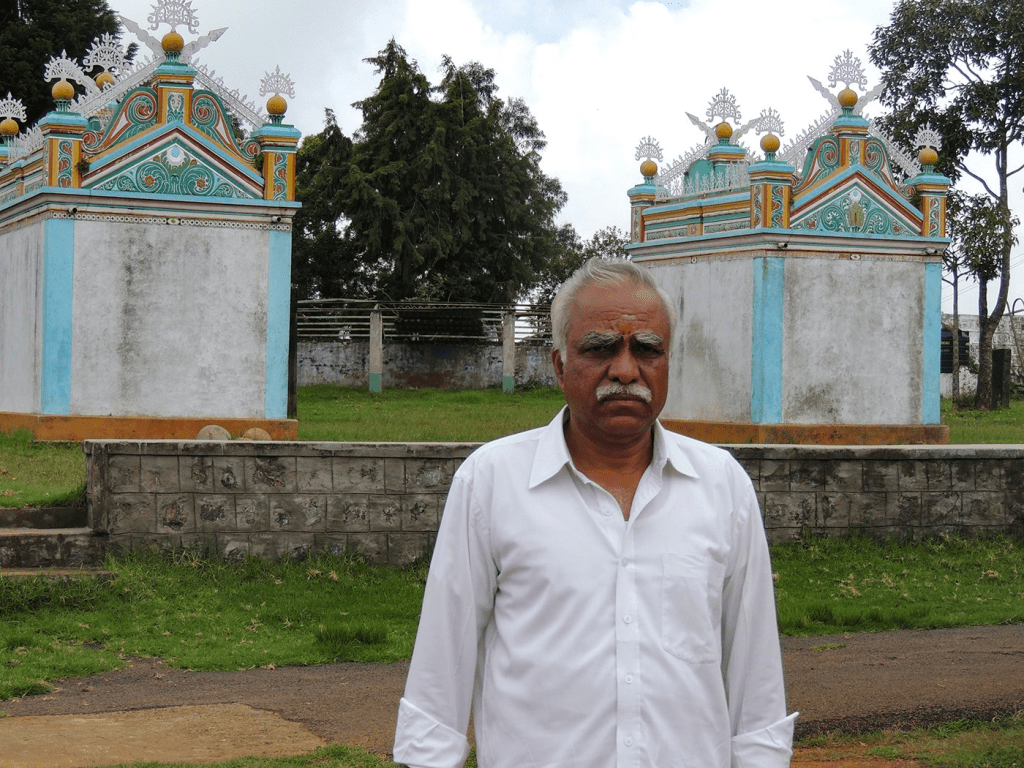

“Only our ladies can make pots,” confirms community elder Mangali Shanmugham, 65, a retired Bank of India manager who has moved back to the Kota hamlet of Puddu Kotagiri. “If there is no potter in our village, we must call a lady from another village to help us.”

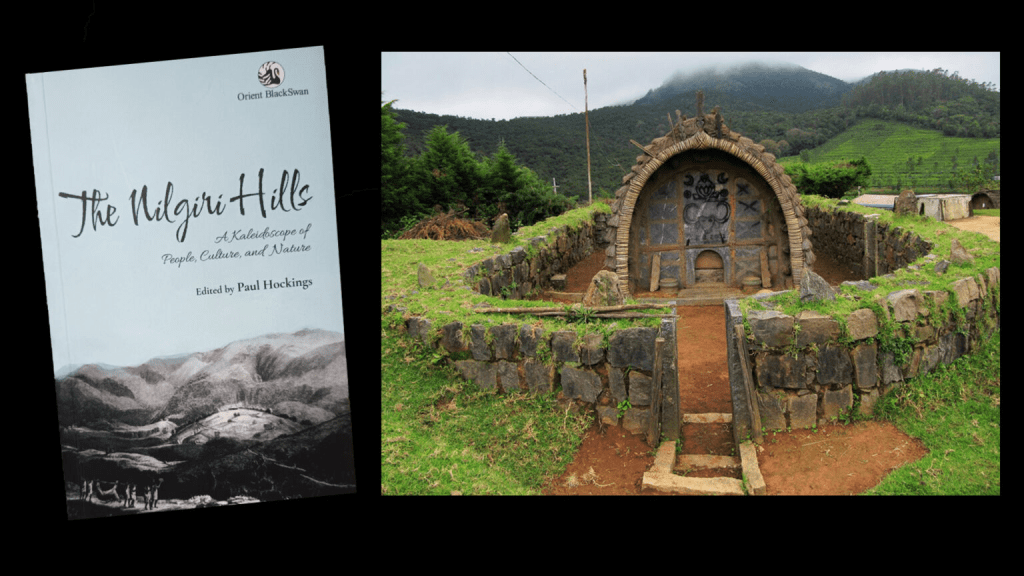

Pottery and religion are intertwined in Kota culture. Clay extraction begins with the 50-day annual festival dedicated to their deity Kamtraaya and his spouse Ayanoor. Sugi made about 100 pots during last year’s festival. “It begins on the first Monday after amavasya (no-moon night) in December/January,” she says. “The head priest and his wife lead the procession to the sacred site for clay. Musicians play a special tune called ‘M ann et kod’ [Take the clay’ ] on the kolle [flute], the tappit and dobbar [drums], and a kobb [bugle], as first the karpmann [black clay] and then the avaarmann [grey clay] are extracted. No outsiders are allowed. The next four months are spent in making pots – the winter sun and air help them dry quickly.”

It is these spiritual links that have kept the craft of pottery alive in Kota settlements, despite the changing times. “Today, young children in our community travel very far to attend English-medium schools. Where is the time for them to watch or learn such things? However, once a year for the festival, all the women in the village must sit together and do it,” says Sugi. This then is also a time for the girls to learn the craft.

A few non-profit organisations working in Kotagari are trying to help revive the Kota clay works. The Nilgiris Adivasi Welfare Association managed to sell about Rs. 40,000 worth of clay artefacts made by Kota women in 2016-2017. They believe this can be bettered if the government funds a clay-mixing machine for each of the seven Kota settlements here. A mixing machine, Sugi says, will indeed help to handle the tightly compacted clay. But, she adds, “We can only work from December to March. The clay doesn’t dry well the rest of the year. A machine can’t change that.”

Reviving Kota pottery has not been easy, says Snehlata Nath, director, Keystone Foundation, Kotagiri, which works with Adivasis on eco-development. “We had expected more interest in the community in taking their craft forward. However, the women want it to remain for ritual purposes. I think it would be good to rejuvenate this craft with the younger generation of women. It can also be modernised by glazing, as we had attempted, and made into modern utility products.”

Sugi, who lives with her husband, their son and his family, says she can sell a pot for Rs. 100 to Rs. 250 to the Keystone Foundation, and organisations which market it, like TRIFED (Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India). Some time ago, along with three other women who helped, she made 200 pots for sale and shared the earnings. But the bulk of the income of her family and that of others in the hamlet comes from farming, and from the jobs they do in Kotagiri and other towns.

The question of whether an essentially spiritually-rooted craft should be commercialised or ‘modernised’ for the economic benefit of the Kota is complex, of course. “It was never a business,” says Shanmugham. “But if someone [from another tribe] requested a pot, we made it for them and they would give us some grain in exchange. And the exchange price varied depending upon the needs of the buyer and seller.”

For Sugi, the ritual importance is supreme. Yet, the additional income comes in handy. As Shanmugham puts it, “The ritual side is non-negotiable. The other side is simple economics. If they can get a substantial amount every month from the sale of pottery products, our ladies will be happy to make the extra income. Today, any extra income is welcome.”

Other members of the community agree. Pujari Raju Lakshmanaa, who worked as deputy manager with the State Bank of India for 28 years before a spiritual calling saw him return to Puddu Kotagiri, says, “Commercial or not, we don’t bother. Kota tribals have always fulfilled their own needs without anybody’s support. We need clay pots for our rituals and we will continue to make them for that purpose. The rest is not important.”

The author wishes to thank N. Selvi and Parmanathan Aravindh of Keystone Foundation, and B. K. Pushpakumar of NAWA for help with the translation.